Why the Best AI Study Tool Isn't the One That Gives You Answers

• Joshua Gans • 4 minute read

When students struggle with a concept, the intuitive solution seems obvious: give them a clear explanation. But decades of education research suggest this intuition is precisely backwards.

Bloom's taxonomy, the foundational framework for educational objectives, arranges cognitive skills in ascending order of complexity. At the base sit passive activities like remembering and understanding. At the apex are active skills: analyzing, evaluating, and creating. The crucial insight is that students learn far more effectively when operating at the higher levels, yet traditional study tools keep them trapped at the bottom.

The research evidence here is substantial. Students who explain concepts to others retain material better than those who simply read it. Those who generate their own examples outperform those who study provided examples. When learners are forced to articulate why an answer is wrong, not just that it is wrong, they develop deeper conceptual understanding. The common thread is effort: genuine learning requires active struggle, not passive consumption.

This creates a fundamental tension for AI-powered educational tools. The natural capability of large language models is to provide answers, to explain clearly, to resolve confusion. But if the goal is learning rather than task completion, providing answers may be counterproductive. The student who gets a perfect explanation feels satisfied but may retain little. The student who must work through her own confusion, articulating and re-articulating until clarity emerges, learns more, even if the process feels frustrating.

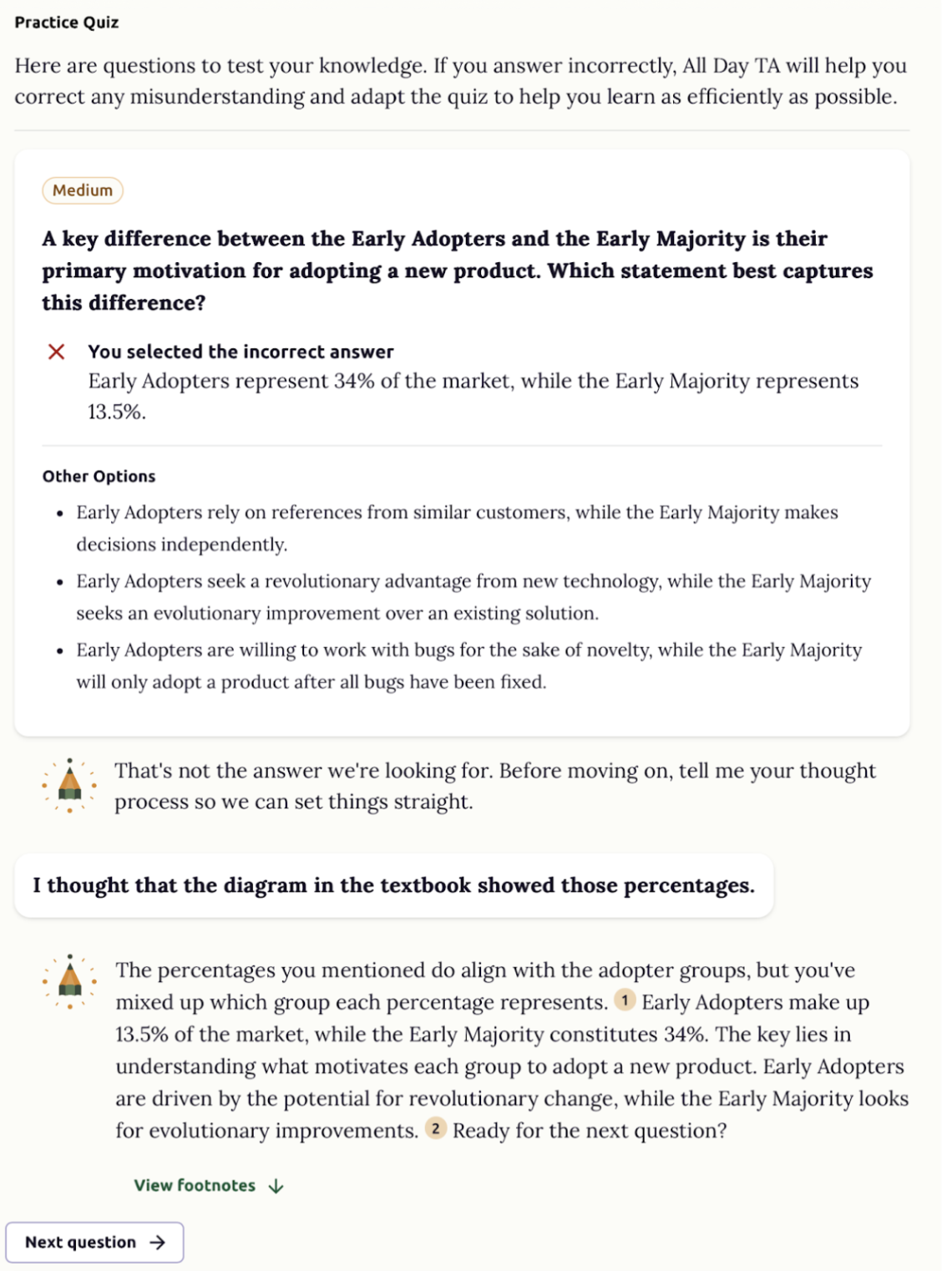

All Day TA's approach to AI tutoring reflects this insight. Our Intelligent Quiz system doesn't simply mark answers right or wrong. When students make errors, the AI prompts them to explain their reasoning, to identify where their thinking went astray. The AI Assistant functions less as an oracle dispensing knowledge and more as a Socratic interlocutor, pushing students to articulate, justify, and reconsider.

This pedagogical design inverts the typical AI assistance model. Rather than minimizing student effort, it deliberately induces effort at precisely those moments when learning is most likely to occur, when the student has revealed a gap in understanding through an incorrect response. The AI's role is not to fill that gap directly but to structure a process through which the student fills it herself.

There's something almost paradoxical about building AI tools that are intentionally less helpful in the immediate sense. Students may initially prefer systems that simply explain what they got wrong. But the research consistently shows that the discomfort of active struggle is where durable learning happens. The best educational technology is often that which resists the temptation to make things easy.

For educators considering how to integrate AI into their courses, this framework offers useful guidance. The question to ask is not "How can AI explain this better?" but rather "How can AI structure an experience that forces students into productive cognitive effort?" The answers to these questions often point in opposite directions.